Rozich is a Seattle native and grew up in a creative household; her father and sister are both artists, and she was raised to view the act of making art as a normal part of everyday life. “My father always told me, ‘Draw every day,” she explains over beers at her house. “And so, I did.” Rozich has a strong work ethic and has always been prolific in her work, but she has honed her focus and fully hit her stride with her current series of images. She credits her fascination with folk iconography in part to the rich cultural heritage and imposing natural beauty of the Pacific Northwest, but her interest also stems from her family’s Croatian roots.

Rozich draws heavily from her Eastern European background, cobbling together elements of traditional Croatian folklore with a hodgepodge of influences borrowed from other cultures. She is a dedicated researcher, and while her patterns give the impression of being effortlessly created, that measured nonchalance is the result of Rozich’s careful search and study of intriguing reference materials. Her interest in patterns was a tangent that eventually became the focus of her works.

“I did a lot of wolves at first,” she says, “but then lost interest because everyone is doing the whole woodland creature thing. So instead, I sat down and started to focus more on the patterns.”

– Stacey Rozich

It’s a joy to talk to Rozich about her influences, and her enthusiasm for her sources is contagious. Rozich gushes effusively about the intricate patterning of Bulgarian Koukeri festival costumes and transitions into equally animated discussions of Russian matryoshka dolls and African tribal outfits.

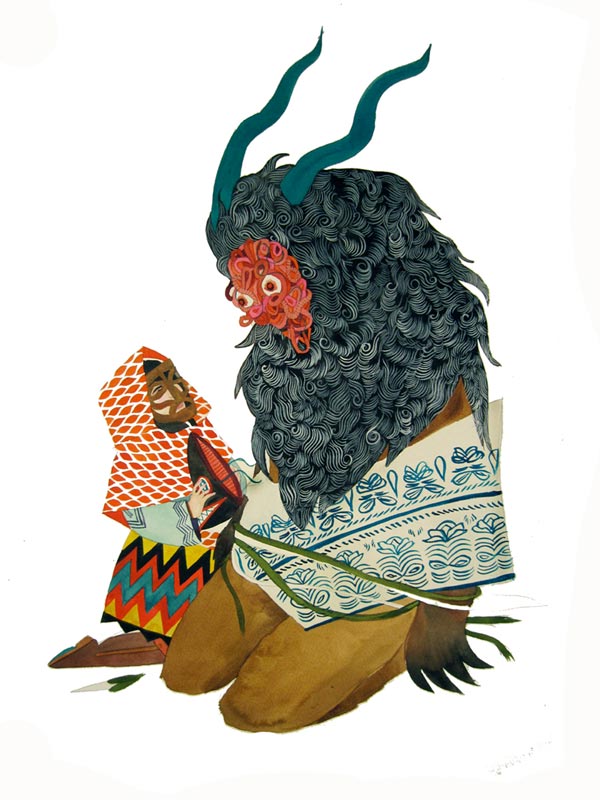

Rozich works with a bold color palette that does not shy away from intense reds and golds, and she incorporates the use of strong geometric design to further call attention to her detailed line work. Her current body of work is concerned with an arresting cast of mythic beings paired with smaller human characters who are dressed in traditional folk garb. Her creatures range from whimsical and serenely benevolent to macabre and vaguely ominous, but they all emanate a sense of deeply-rooted, inhuman power.

Rozich explores this dynamic, explaining that she is interested in “the relationship between the humans and the spirits and nature and how they interact.” She describes the folklore, saying, “A lot of it is hostile, and a lot of it is really curious. Some of them are pretty brutal — a lot of killing, a lot of arrows going through skin — and then a lot of them are really sympathetic. A lot of the human characters are trying to help, to maybe question and seek wisdom from these figures.”

While the specific creatures vary in each of Rozich’s pieces, there is a strong sense of narrative continuity running through all of her work. This element of storytelling is something she learned at an early age; much of Rozich’s inspiration comes from the imagined worlds of her childhood. “I used to write a lot of stories as a kid,” Rozich explains. “They would just be really long meandering fairytales, and then I realized I maybe wasn’t that good at it. As I got older, I learned that if you can convey a story with an image, then you’re good; you’re golden. So I focused on having this background narrative that wasn’t quite obvious, yet each piece has a little vignette — a little drama in it.”

Perhaps because of this sense of visual storytelling, Rozich’s work skirts the line between fine art and illustration, and she is sensitive to the borderline territory she inhabits. “I see fine art as a mixed blessing,” Rozich explains. “You can learn to talk about your work and have this wonderful vocabulary about your process, but I think in terms of trying to market yourself, that’s something that’s not a priority for fine artists. And it definitely is for me — because my father was an artist, and I saw how he worked so many jobs to support our family and then do his art on the side. And it was so necessary for him, but it was always a struggle.”

Rozich’s pragmatism and desire to be marketable led her to the California College of Arts in San Francisco, where she spent two years studying Illustration. While she speaks positively about her time at CCA and praises the amazing sense of community, Rozich felt somewhat out of place in the program. She ultimately left due to a combination of concern over cost and a belief that her process would be better served outside of school.

“I don’t know if I would necessarily tell people to go to art school,” she confesses. “I feel like my experience was wonderful, but I think I’m better off having left.” She pauses for a moment and jokes, “Just accrue some really bad debt for a year and work it off!”

In spite of having left an Illustration program, Rozich still feels most at home placing herself in the world of illustration. “I think it has a broader scope and reaches a lot more people, which is something I really like, whereas fine art — well, a lot of people are trying to tell me that my art is going in the fine art direction, but nope!”

Rozich has a similarly conflicted view of her relationship with Seattle, and with the Pacific Northwest as a whole. “I have a really good network of friends and family [in Seattle],” she explains, “but I do think I lack a little bit of the support structure I had when I was in the Bay Area and [being] surrounded by a lot of like-minded artists. The Northwest is a good, nurturing place for artists to go onto other places. I think that’s what I’m planning on: moving, in the next year.”

Rozich initially toyed with the idea of going to New York, but eventually settled on a move to San Francisco, a city she has always felt emotionally drawn to, and where she has already established firm creative connections. Rozich draws great resolve from the strength of her community and stresses the important place her friends hold in her creative process.

INTERVIEW CONTINUES BELOW

“I wish I could have an island of all my friends and the people I’ve met who I think are really talented,” she tells me, “and I’ll just pile us all together, and we’ll all live in a big longhouse and have bunk beds and have big communal meals…” Rozich pauses and laughs. “I guess what I’m saying is that I’d create a co-op, which I’m not actually really into; I would probably get tired of it. But everyone I love is spread out all over the country, so I just wish they were always in the same place!”

Rozich is an intelligent, thoughtful artist on the cusp of an exciting point in her career, but she is not immune to the bouts of crippling self-doubt that are part and parcel of any artistic path. Rozich speaks candidly of how she rides out her waves of pessimism. “I go and scream into a pillow,” she laughs. “I think I have to step back from what I’m doing and just take a breather. I do get really wound up in what I’m creating… and sometimes I think it’s very unnecessary. There are these extreme highs I have when I’m creating something, and then these really lows where you really are just rethinking your whole process. It’s like being in an abusive relationship sometimes; ‘It’s not always like this, I swear!'”

Moments of doubt notwithstanding, Rozich’s current endeavors are being met with overwhelmingly positive feedback. Her recent show, Patterns of Renewal, at Pun(c)tuation Gallery, garnered a great deal of attention from the Seattle art community, and more than half of the show’s twenty pieces sold on opening night. Rozich has also been attracting international attention through her blog, and her work has been published in a potpourri of magazines and journals. CityArts magazine’s Joey Veltkamp recently dubbed Rozich the artist [Seattlites] are about to start paying attention to.

It’s a pity that Seattle is about to lose Rozich to San Francisco, but there’s always an aspect of excitement that comes from any relocation. “I want to move somewhere where I’m challenged and uncomfortable and out of my element,” Rozich explains. “What comes out of it is ultimately weird and rewarding.”

mysterymeats.blogspot.com